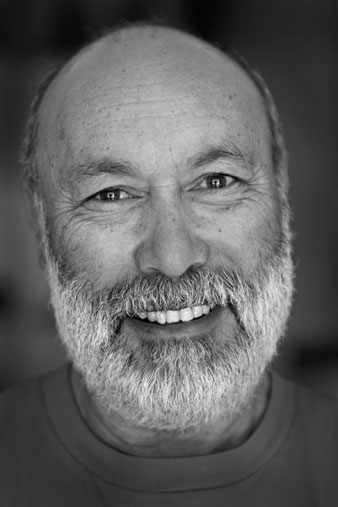

Able Seaman torpedo man, Able Seaman and Electrician’s Mate, Royal Australian Navy

Wyatt Earp, 1947

There were 37 of us in the crew, plus the scientists, including Dr Loewe, a German geologist and meteorologist. He was a real scientist that fellow. The officers and scientists ate in one mess, and we ate in another. There weren’t any problems at all with that. We got about 20 miles from the land of the Antarctic continent in the Wyatt Earp. We couldn’t get any closer because of the thick pack ice.

Life on board the ship was quite comfortable, considering. My berth was a double-decker. We had some sort of military sleeping bags. I was used to that kind of living, we were used to living in one another’s pockets all the time. You’ve got to get on together.

I’d have liked to try my hand at fishing down there but it was a little bit too cold for that. You couldn’t stay outside for too long. Although the ship was wooden, when it was 8 degrees (C) outside, with all of us in there it was 23 degrees down below in the ship.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

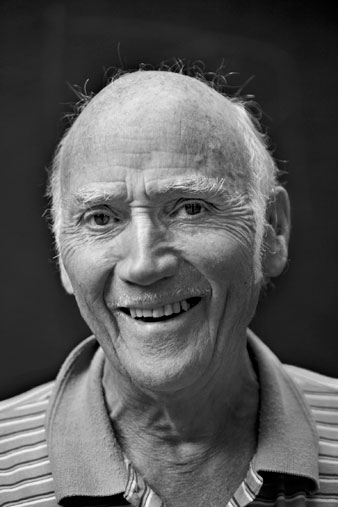

Radio Operator, Postmaster

Q51, M54

Before we left for Mawson we all volunteered to have our appendixes out, because the year before, the doctor on Heard Island had to be brought back to Australia to have his out. It took two ships to get him back.

Mawson station was officially opened on 15th February 1954. We built it from scratch. If there were blizzards as we worked, we’d have to dig out our huts before we could continue. We had used aerial photographs taken by RAAF Auster aircraft to find a spot where we could build the station on bare rock. The Americans built theirs on ice, and they’d disappear every now and then.

There was an exploration trip east of Mawson that was planned to take a couple of days. We travelled on sea ice, but after about 100 miles the sea ice broke out. We got the Weasels [tracked vehicles] ashore but we were stranded there, at Scullin Monolith, for about a month before the sea ice refroze. The officer in Charge had experience in this though and told us what to do and what not to do, and we had a caravan full of tinned food and other supplies.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

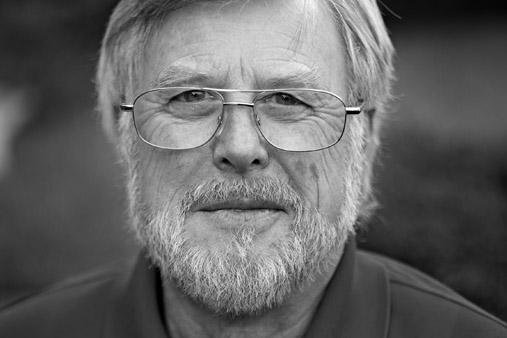

Weather Observer

H51, M54, Q56, D57*, W59*

We had to level everything off at the site and build foundations and the rest of it. We were living in makeshift camps under canvas or in the Weasels [tracked vehicles]. The ship stayed there until we were relatively well established. You get used to living in a tent. It wasn’t too bad, the cold. We had plenty of warm clothing.

I was the only Met man there at Mawson that first year, and the job was non-stop.

I was usually the official photographer for trips I was on. It was always a cinecamera. I also had a Leica and a 21/4 square Rolleiflex single lens, and I had my own camera. It was black and white films in the early days. You had to make sure your camera was warm enough to survive a few minutes in the open air. I nursed many cameras inside my clothing.

You built strong relationships with some people, and others, you tolerated. That’s life down there. It was just a big adventure. There were some bad times but you survive them anyway. If I were young enough I’d do it again, no question about that.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

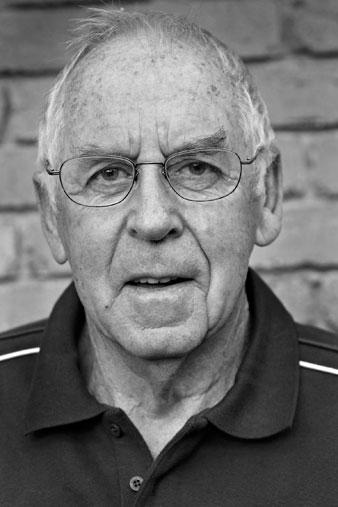

Radio Operator

Q50, M55

At Mawson in 1955, the main purpose was to further develop the station, which had been set up the previous year, and to support the expeditions. I was one of three radio operators. This was shift work, over 24 hours.

You were dressed up and rugged up, gloves and all. For hot water, we were dependent on the exhaust pipe of the diesel engine that provided electricity, and you had a day a month to wash clothes – and yourself. It went reasonably well, and because of the low temperatures you didn’t become too obnoxious – at least everyone thought they didn’t.

One of the great emotional experiences down there was seeing the auroras. They were very beautiful. They’re wonderfully thread-like things that shift like a huge beaded curtain.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Plumber

Q75, D78

It was my responsibility to keep the plumbing going on the station. I applied myself to it and came to realise that people respected that, even though I was only 22 or 23. It did wonders for me, and my self-confidence really soared. The experience on Macquarie Island broadened my mind and told me that there’s more to this world than your job.

My first impression of Antarctica was of an incredibly harsh, bloody barren place. When I first landed at Davis, I thought, ‘Good God, what have I done?’ But I had one of the best times at Davis. I did a lot of things there, such as collecting and tagging fish for the marine biologist. They had sent us some hoop nets for this but the netting was too big – you could have caught a whale in those things – so I made up my own.

It was fun to be involved with the scientific program. Where else would you get the chance to live in a polar pyramid tent that can withstand enormous winds?

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Radio Officer, Radio Supervisor

Q56, M58, D61

In 1958 and ’61 I trained as a surgeon’s assistant, and that was very handy as we had an appendicitis case during the changeover at Mawson. I helped the doctor at the operating table, and the guy survived.

I was most excited by the prospect of working with the biologist. I helped count, brand and weigh elephant seals, and band petrels, penguins and albatross. I collected lichen, and had one named after me – Parmelia brownii.

On a seismic trip in 1958 I was out in a Weasel as the scout vehicle, detecting crevasses. We got into trouble at Hordern Gap in the Framnes Mountains. The tractor was hanging perilously on the edge of a crevasse by its tracks. We had to go back to Mawson to get suitable timbers to get it out of the crevasse or it would have disappeared out of sight. Blow me down if Jim Blair didn’t slot the second tractor down a crevasse as well. It took us three weeks to dig it out. Then we went back to the first one and dug that out too. You’d think, ‘Oh, time to give up,’ but you don’t. You see it as a challenge. That’s what you went down for.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Diesel Mechanic

M77, Q79, C83

I had surgical assistance training before going down south. On Macquarie Island we had an emergency situation because poor old Roger Barker had fallen off a cliff and he was very badly injured. We had to do everything we possibly could to help him and do the very best for him. Unfortunately he passed away as a result of his injuries when he got back to Australia. It was very tragic.

I did the rounds to the magnetometer building and the seismic vault with Kevin Wake Dyster, our geo-physicist. Throughout the year I tried to spend some time with all of the boffins to find out what they did, how they did it, what their job was, why they were doing their job. It gave me a different focus and outlook.

My Antarctic experience enhanced my career, because now I’m not afraid to take on anything. Down there you’ve got to make it work because people are relying on you, and if it’s busted you’ve got to fix it. In the automotive mechanical engineering industry there are challenges every day. I find myself saying all the time ‘if this was in Antarctica, what would we do?’

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Diesel Mechanic

C72, M74, M78, M83, M86, M88

I did an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner and then got into the diesel fuel injection side of the trade. The mechanical section of a station is really the heart of the whole business. The power station runs the place. If that stops the whole show is over, you get cold, there are no lights. It has to work, you make the station go.

We’d go inland and prepare the camp and landing strip with the tractors and we’d set up the living tents and vans and prepare the whole outpost for the people to do the research. They’d come in helicopters and Twin Otter aircraft and they could start work immediately.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Carpenter

Q66, D77*

Before we went to Davis, the Director called me into his office and said,‘ Alan, I want you to find Sir Hubert Wilkins’ lost records that he left there in 1939.’ We had a rough idea where they were, at a place called Walkabout Rocks, about 30 km from the main station. We went up there on the sea ice in late August so there wouldn’t be much snow cover, but at that time you don’t have much light. We didn’t find them the first time, but I had a chance to reconnoitre the area. When we were to go back, I couldn’t go myself but I had selected for the team a man we used to call ‘Magic’, because he was lucky. And he found them in a cairn of rocks. There was a flag in it and a proclamation saying Wilkins claimed the land. That was of great interest for everyone in the group, it bound us together.

I want young people to know that you don’t have to be a scientist to go into these wilderness places. The scientists can’t function properly until they have their buildings up and fitted out.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Station Leader

C88/89, M89*, D95*

Four of us did a 350 km husky trip from Mawson around the coast to Kloa Point. This trip was rarely done, and only one other woman had done it before me. It took ten days to get to Kloa, camping out each night on a rocky outcrop or an island because there’s always the danger the sea ice will break out. It was physically really, really challenging. Some nights it was minus 20 and you’d wake up with ice around your face. It was an amazing trip – so silent. It’s hard to go anywhere in Antarctica without the noise of the station generators or vehicles, but to travel by dog sleds … Working together in a small team, the partnerships you had with the others and with the dogs were quite amazing.

Seeing your first iceberg from kilometres away is like seeing your first whale. There’s something about nature that’s so awesome. You’re on the edge of this continent on the bottom of the world – I still haven’t lost that sense of awe.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Radio Technician

Q56, M58, C78*

Mawson was entirely different from Macquarie Island. Macquarie was a cool place, and windy, with rain and a bit of snow in the wintertime. But Mawson was cold, and there was no smell, unlike on an island where the smells waft out and give off an odour. The Antarctic was clean, crisp and very invigorating.

In the late ’50s, while the Cold War was going on, we had Russians at the neighbouring Mirny base. They were terribly friendly. On the way down we called into their base and were welcomed like long lost families. Everyone gave us bear hugs – very embarrassing. They even had an American on their base. We were in communication with other Antarctic bases too – Japanese, Belgian. There wasn’t a Cold War down there.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Chef

Q78, M85

I learnt a bit about hydroponics and growing vegetables and I had a little A-frame down there. I planted seeds in November when I first arrived and ended up with tomatoes and lettuce in October. Other things grew more quickly, like parsley and chives. Carrots and radishes didn’t grow at all.

For midwinter I made a cake in the shape of the Continent, with lots of islands on the side, nicely decorated with peaks here and there, and a little Nella Dan on the edge of the sea ice. I left it on the bench overnight but the window wasn’t quite closed. The icing was ruined the next morning because we’d had a blizzard – but these things happen.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Weather Observer

H53, M55, M & D58

We all had more than one real reason for trying to get down there. In my case it was adventure, and trying to climb mountains, which I was very keen on in those days.

Before I went down, I did Met Observer training at the weather bureau. I was pretty raw. I learnt how to use the radiosonde machine, which is a radio that is sent up, something over 100,000 feet, on a balloon. We started the first radiosonde flights for Australia, and these are now the longest-running radiosonde flights on the Antarctic continent. The Met work was fascinating stuff. It gives you an idea of what it’s all about – makes you feel part of the global scene.

At times I felt completely at one with the surroundings. Once at Davis, on a Saturday night, I was just standing at the open door looking out over the sea ice. There was a chain of icebergs slowly moving across the horizon and the low sun had turned them gold … and the slow movement of Beethoven’s third symphony was playing, and everything just fused into one and I felt I was part of it, part of the whole scene.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Radio Supervisor, Radio Physics

M55, M59

My main job was repairing communication equipment. Everyone had to help with setting up buildings, and building works were ongoing. The blokes were pleasant. We didn’t have any squabbles, it was alright.

The physics hut was quite a distance from the mess, so when there was a blizzard you had to use the life line to walk from one building to the next. I’d phone the mess to let them know I was leaving the physics hut: ‘I’ll be in the mess in about 10 to 15 minutes. If not, come and look for me.’

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Electronic Communications Technician, Radio Supervisor

M60, W63, W67, C69, C74, M77, Q83, Q85, Q87, Q89

I loved the job, I loved the work, I loved the place. Your achievements were in the job – you could see the results of your efforts.

In the beginning, the radio operators sent the personal, scientific, weather and administrative communications – kept the messages and traffic flowing – all in morse code. With email, radio operators became redundant, namehough they do still have them in summer to communicate with aircraft or scientific field parties. I saw it go from morse code to computer satellite.

We had really good chefs down there. The first one used to be the chef for the Governor of New South Wales. That’s how I became ‘Chompers’. He’d say, ‘That bastard can chomp’, because I’d come back for seconds. Then it was ‘midnight Chompers’, ‘afternoon Chompers’, ‘bar Chompers’: everything to do with eating, I was ‘Chompers’.

One time, we’d been out to the edge of the Vanderford Glacier to see the crevasses. We were walking back, very relaxed – we’d taken all the ropes off – and I went ‘whoosh’… I was down to my armpits in a crevasse. I called out, ‘Oooh, guys …’ and they said, ‘Are you alright?’ I pulled myself out, turned around and looked down this ruddy hole – it was 60 to 70 foot deep, disappearing into the blue. My pocket zip was open, and as I leaned over, a camera went ‘whoosh, tickle, tickle, tickle’ down … and I never saw it again.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Carpenter

C73

The thing that surprised me was how many other people on the station knew something about carpentry, or other trades. I could weld a bit, I certainly had no trouble doing plumbing, and I would have a go at electrical as well. Concreting, steelwork, sheet metalwork, flashing, virtually anything – we were the people there and really you just had a go at it. …the main carpentry jobs were finishing off the emergency powerhouse, fitting out caravans for fieldwork, making shelving, repairing buildings if anything broke down, and finishing off small buildings. There were different things going on all the time. Quite often you were working 15 or more hours a day. I can remember helping the diesos, and vice versa.

After going down, you probably think a bit more laterally about how to solve something. Instead of, ‘I haven’t got one of these’, it’s, ‘what can you use that will do the same job?’ A lot of the work I’ve done since has been along those lines – certainly site supervising in building.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Electrician

D82, Q84

One of the jobs the electricians had to do at Davis was look after the toilets. They were gas operated and had fans. There was a gas leak and I went and fixed it up. When I closed the lid to make sure it was going, the whole building exploded – I blew the walls off, and I was a bit singed. The toilets that blew up were called ‘destroilets’. There are a lot of toilet stories in Antarctica.

We’d go on jollies. Jollies are when you go away from the station for recreation and have a bit of time away. They’re good fun – although for a lot of the trips we had to do weather observations at different places in the Vestfold Hills.

We used to go out with the biologists, mainly day trips or a few days overnight. They used to tag seals and stuff like that. You’d try to get the tag into their back flipper. It was a bit of a process. It could be dangerous and you had to try to get them when they were a bit quiet. The seals seemed quite big.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Diesel Mechanic

Q61, M63, M65

As part of the maintenance crew, my job on Macquarie Island was to keep the diesel generators running for scientific purposes. We had cooks, mechanics, plumbers and so forth, but that year no carpenter. I was quite handy with a hammer and saw so I became the carpenter around the place. I and some of the others oversaw three igloo huts being erected.

At Mawson station, as Senior Diesel Mechanic, I ran the power house, and Ken [Shennan, ‘Scruffy’] and Ted [McGraw] did all the vehicle and ancillary work. I didn’t do carpentry at Mawson, but I did do quite a bit of plumbing and some concreting work. We had a machine that blew hot air onto the concrete while it was setting, as naturally the water would freeze pretty quickly.

The fellows quite enjoyed my cooking, but that wasn’t always the case. One guy cooked a leg of lamb, but it was still bleeding, and all you could hear around the table was ‘baa, baa’. There was no mercy.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Radio Technician

M67, C69

I was inspired as a schoolboy to go to Antarctica. Our chaplain had been down on the first ANARE expedition in 1948 as a cosmic ray physicist, and for Religious Instruction he used to bring his stuffed penguins and give us slide shows to keep us occupied. When I first started working I was a radio technician for the PMG [Postmaster General]. I knew they needed radio technicians in Antarctica, so I applied to go as soon as I was qualified.

You had to use what you had there – you couldn’t go to the shops. I made an ice yacht, and we’d spend a couple of hours before dinner yachting on the ice. To make it, I got a big canvas tarpaulin, cut it into pieces and sewed a belly and pockets into it. The steering mechanism was the handle of an axe on a bolt and some ice skates, the mast was a piece of aluminium scaffolding pipe, and the frame was a couple of big pieces of wood. I used a bit of climbing rope for a pulley to hold the sail down as you careered around in the harbour.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Diesel Mechanic

M63, W65, Q67

There were about 25 of us living at Mawson my first year. There were four living quarters, each with eight dongas about two metres long – your own little room. The bunk was upstairs, with a little writing desk and a table underneath and a wardrobe-like thing. That was your world.

You’d check your fingers and toes for frostbite, and when you came into the warm with it, the pain was shocking. The only weather that would have us frightened was a white-out. You get this reflection when the sun’s rays come through the clouds and bounce off the white ice and back up to the clouds. It’s not foggy, but you don’t know where the horizon is.

There was a sweep for when the penguins would come back to nest in the rookeries. One morning after breakfast Brian ‘Red’ Ryder looked out to sea and said, ‘Look, I told you they would be early this year.’ There was this little black spot about two miles out. He won the prize, but three days later that single lone penguin was still there. Red had put a stuffed penguin out there. He was a shocker.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Plumber, Carpenter

W68

We had to fill the heating system with water mixed with glycol, an antifreeze. We didn’t know that glycol contains a lot of alcohol. I was stoking the fire when the alcohol blew up and flung me about 20 feet away into a snowdrift. The others came rushing up. I was lying there looking like something out of a cartoon, with a black face.

The dogs were a wonderful experience. After about May, the dogs are the only other living things there. The penguins, the seals have left, the sea’s frozen over, and the sun’s only coming up a few hours a day … and you’ve only got the dogs. They are wonderful companions. Going out with them, all you can hear is their panting and the shwoosh of the sled on the ice. It’s just so exhilarating.

I don’t think anyone who goes to Antarctica comes back unchanged. In later life when I got involved in politics, my experience in Antarctica helped me in understanding and being tolerant of other people.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Electrician

Q75, M77

There were a lot of other jobs I had there. As the electrician I was a fire officer in charge of fire fighting, and I was the projectionist.

I was a surfie from way back and I’d surfed all over the world, so I thought I might as well surf at Macquarie Island. I went out a few times. ’ The water was cold and there was a lot of kelp, but we did it. I suppose that was pushing the boundaries. You did things like that.

My advice to young people is to open your mind up, and get going: ‘Sit down, knuckle down, get your education, and then go,’ and the world will just open up.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Radio Operator

Q63, M65, W67

Before I went down south, I was trained to be the doctor’s assistant. Another role I was asked to do was postmaster – philately was very important as the Antarctic stamps were coming through. I was also the assistant to the biologist who was studying seals. I had to help with the seal counts and we did a fair bit of weighing of the animals, including the pups.

I had to learn how to drive D4 caterpillar tractors before going, as I was to take part in the summer traverse towards the end of ’65. During the survey we got blizzed in and one of the snow tracs went down a crevasse – it was ‘slotted’. We had a big job to get it out. Things happen and you’ve got to rely on who you’re with, don’t you? You just have to accept, ‘Okay this is the situation we’re in. How do we get out of it?’

When we were blizzed in somewhere along the track, I thought I might make a batch of scones. So somewhere out in the middle of the ice on this field trip we had a little feed of scones and butter.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Meteorological Observer, Dog man

M75, M77, M93

I joined the Bureau of Meteorology in 1973 and discovered that I could go down south. When I heard they still had dogs down there I wanted to get involved with them because of the historic context of the early exploration era.

I preferred being out in the field with the dogs and being able to camp out instead of taking a vehicle. The dogs were an integral part of the base and of the program of scientific work. We had to go out to the rookeries, do the census work, take photographs and try to make a visual count.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.

Radio Officer, Communications Officer, Dog man

M77, M80, C88*

Communications Officers tuned receivers and transmitters, plugged aerial patches in, sent and received morse code. It’s become more technical and satellite-based now. In the old days we had racks and racks of short-wave high-frequency radio equipment and massive antenna farms and it was all done with morse code and teleprinters.

The wind at Mawson sings to you through the aerial wires. There are particular kinds of radio masts that look a bit like organ pipes. They are a kind of tubular steel with holes in, so between those and the guy wires and the aerial wires that are strung through the air, when the winds are hooting, Mawson has the weirdest ethereal kind of sound. I loved it.

The dog man duties were extensive and constant. You have to take them out for a run because that’s what they live for, and you run with them. It’s amazing how far you can run with the full kit on – mukluks and ventiles. It’s hard work but at the end of the day no matter how cold, wet and miserable you feel, you just feel utterly alive.

*This text is an abridged version of the story featured in the exhibition.